harrison mäe

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

I can’t get over it.

The thylacine is dead.

I can’t get over it.

The thylacine, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, is an extinct carnivorous marsupial. It previously lived on the Australian mainland and the islands of Papua New Guinea, where it died out roughly 5000 years ago prior to the arrival of Europeans.1 It persevered on the island of lutruwita/Tasmania, where it is estimated over 5000 individuals remained at the point of European colonisation.

This photo of a thylacine holding a chicken in its mouth was taken by amateur naturalist Harry Burrell in 1921 for the Australian Museum Magazine. Burrell’s photo is widely considered to have bolstered understandings of thylacines posing an active threat to livestock. Recent analysis has revealed however that the photo was staged, and actually depicts a taxidermied thylacine specimen posed on a set.2

Contemporary accounts described the thylacine as a shy and reclusive animal, semi-nocturnal and cautious of humans. It was known to shelter in closed forests during the day, only emerging at night to hunt small mammals and birds in heath and scrubland. Despite its reclusive nature, European settlers saw the thylacine as a threat to agricultural interests. Photographs were staged and doctored to incriminate it as a poultry-thief, and the moniker ‘Tasmanian Wolf’ helped to identify it as a threat to livestock. This quiet animal was viewed as a vicious predator of sheep and poultry, and was relentlessly hunted.

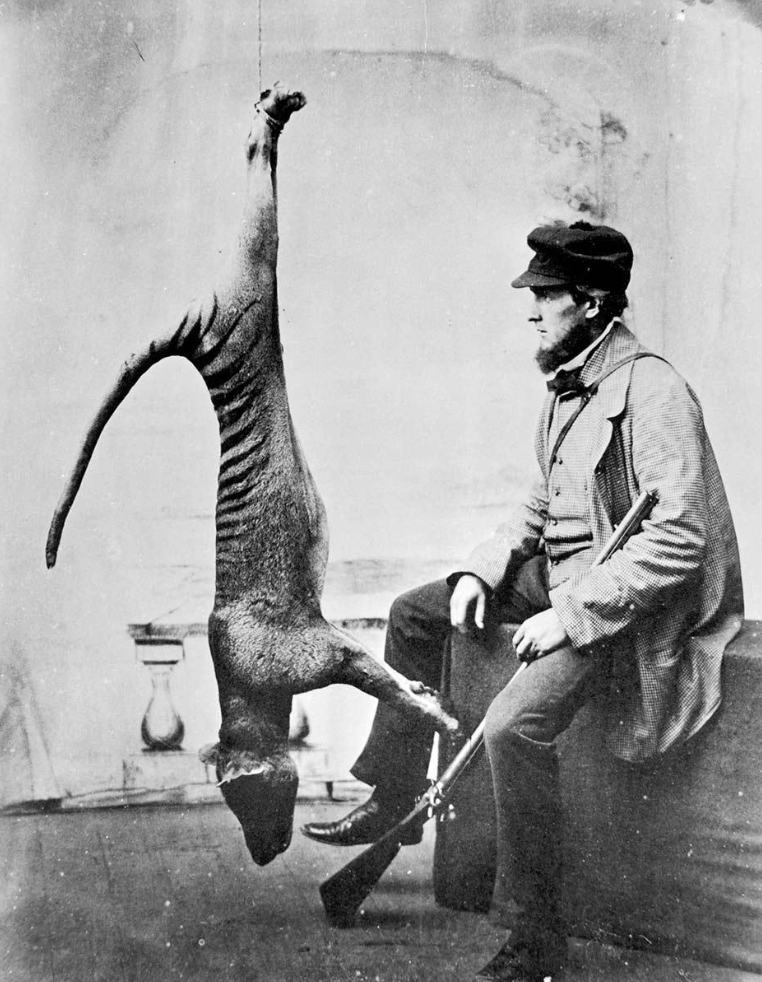

Hunter pictured with a dead thylacine, 1869. 3

Bounty systems for thylacines were established, with farmers paying money for thylacine skins.4 In 1888 the Tasmanian government also introduced their own system; £1 per adult thylacine and 10 shillings for juveniles were paid out for each animal destroyed. Over the course of 21 years, the Tasmanian government paid out more than 2184 bounties for destroyed thylacines. Between the official government program and more informal bounties, it is estimated that over 3,500 thylacines were killed through European hunting. This, combined with extensive habitat destruction and introduced zootopic diseases, led to the rapid decline of the thylacine.

Pictured here is farmer Wilf Batty alongside the last known thylacine to have been shot in the wild. He claimed to have shot it in 1930, after seeing it in his hen house.5

![]()

This photo depicts the thylacine killed by Wilf Batty. This photo was taken in the moments after it had been shot, as it lay dying.6

This photo depicts the thylacine killed by Wilf Batty. This photo was taken in the moments after it had been shot, as it lay dying.6

By 1936, there was only one known thylacine. A lone female, kept in Hobart’s now abandoned Beaumaris Zoo. You can watch her in video; 63 seconds of black-and-white footage, recently colourised. You can see her stretching her infamous jaws into a yawn. Repeatedly pacing the length of her enclosure. Laying down. Resting.

In the early hours of September 7th, 1936, this lone female passed away.7 It is believed she died from exposure. Kept in a too small a cage, with too little shelter, by those who cared too little to ensure she was safe, and warm.

Alongside the passenger pigeon and the dodo, the story of the thylacine’s demise has become a cautionary tale, a fable warning of the impact mankind has on the natural environment. National Threatened Species Day is observed on the anniversary of her passing, and she has become a symbol for conservation and environmental protection in Australia and across the globe.

In 1936 however, the passing of our lone female was received with little fanfare. At the time of her death, the museum had an active £50 bounty to be awarded to anyone who could capture another live thylacine. It was believed that there were still individuals out in the bush, and it was only a matter of time before another one was captured. No one thought that she was the last one. After her death, our lone female’s remains were given to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG). She was skinned, and taken around the continent as part of a touring exhibition.

The stretched skin of the lone female, as kept at TMAG.8

She was shown to schoolchildren, her appearance a break from the doldrum of everyday classes and activities. An interesting lesson in Australia’s strange and foreign wildlife.9 During these visits, our lone female was put on show. She would be stretched and laid out on the floor. She would be sat on, and patted.

Eventually she was returned to the museum and left in a storage cupboard - unmarked – where she would remain for decades, forgotten. She was only rediscovered recently, during an audit of the Museum’s specimens.

She was made a floormat before she was made a martyr.

The thylacine is dead.

I can’t get over it.

Maybe it doesn’t have to be forever.

I don’t want it to end.

In 2022 – nearly 90 years since the death of the lone female - a team at the University of Melbourne announced that they had partnered with US firm Colossal Laboratories & Biosciences to ‘de-extinct’ the thylacine.10 This followed a study published by the university team in 2018, in which they were able to successfully sequence the genome of a thylacine with 99.99% accuracy. Through a process of computational biology and gene editing, Colossal aims to bring the thylacine back from extinction by transposing the sequenced genome onto that of the thylacine’s closest living relative – the fat tailed dunnart. Acknowledging the role of European settlers in driving the thylacine to extinction, Colossal asserts that they are determined to give the thylacine a “second chance at life”.11

Collection Number C5757.12

This fully sequenced genome was extracted from a specimen in the collection of Museums Victoria: No. C5757 – a 108-year-old female specimen, taken from her mother’s pouch. Following the completion of the University of Melbourne study, the entire genome of C5757 was uploaded to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA), open access. You can download it if you like.

BioProject PRJNA354646

BioSample SAMN06049672

Access via: https://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/?view=run_browser&acc=SRR5055306&display=metadata

I wonder if it’s really possible to view DNA as a code, a cipher to be cracked. Is what makes a thylacine really the particular manner in which ones and zeroes are ordered? A program lying latent, simply awaiting activation?

Perhaps we can view museums/galleries/private collections as data centres. If the genome can be read as a code, then perhaps museum specimens exist as hard drives, data to be loaded when the original program fails. As I type this I cast my eyes to the 1TB SSD drive currently plugged into my laptop’s USB port, a backup drive should my original file be lost. Soon, museum specimen C5757 might perform a similar function.

For over a century she has remained submerged in ethanol, kept in a jar on a dusty museum shelf, for safekeeping. Now she is stored in a different way. Archived in the internet, zipped and compressed she lies in stasis. Floating in the cloud, awaiting activation.

Did they encode it all? The particular prickle of her whiskers? The gentle caress of stripes along the slope of her back?

I imagine the way she might have grown.

What would it have been like when she poked her head out of her mother’s pouch for the first time? The sharp southern air of lutruwita would have been quite a shock against the gentle wet of her nose. Maybe she would have wriggled back around, into the fleshy folds of her mother, the unknown of the outside world a challenge to be faced on another day. For now the sweetness of her mother’s milk would keep her sated, and the warm embrace of her pouch meant the comfort of home.

Maybe she had siblings. A brother, and a sister. When their mother’s pouch grew heavy, and the world beckoned them onward, would they have ventured out together? Felt the damp moss and cool earth under the softfall of their padded paws? They might have seen the warm ochres and lush greens of the Gondwanan rainforest before them, the gentle chill of fog clinging to their rufous fur. Perhaps they would have looked back at their mother, waiting for a nod of reassurance, before venturing forward.

As they grew more confident, would they have played together? Maybe they would follow their mother’s lead in a mock hunt. Laying low in the ferny undergrowth, before bounding forward in a lop-footed gait. I picture C5757 as especially cheeky, playfully yipping as she’d chase her siblings through the scrubby heathland. Nipping at their heels with a grin in her eyes she’d finally catch them, and they’d tumble over one another in a great big pile. Perhaps they’d bite at each other’s ears, squealing with glee, the authoritative cough-bark of their mother the only way to cut through the mischief.

Maybe in time, she would have had pups of her own.

I long to hear her.

I don’t want it to end.

Thylacine_C5757_WGS;SRS1819160 is downloading.

0% of 37.14Gb complete…

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

A fatal error has occurred. Failed to run.

This program will now be terminated.

︎︎

“One way to live and die well as mortal critters in the Chthulucene is to join forces to reconstitute refuges, to make possible partial and robust biological-cultural-political-technological recuperation and recomposition, which must include mourning for irreversible losses… There are so many losses already, and there will be many more.”- Donna Haraway

We must become-with the dead and the extinct. That’s what Donna Haraway argues. Rallying against anthropogenic modes of existence in Staying with the Trouble, Haraway urges us to move towards a more “tentacular” existence in her proposed Chthulucene.13 An era where we ‘make kin’ - become-with, compose-with - the myriad of biotic and abiotic organisms that exist on this earth.

In articulating this shift away from the current Anthropocene or Capitalocene, Haraway acknowledges that renewal and regeneration cannot come from myths of immortality.14 From climate change to ecosystem simplification, the depletion of rivers and lakes to nuclear pollution, the collapse of major systems has already begun. The name of the “game” on earth has changed forever. While we can work to make this epoch as short and as thin as possible - work collaboratively towards a future in which all earth-bound organisms can flourish - we cannot undo what has already been done. We must mourn for that which is lost.

The thylacine, by all accounts, should be here today. Its extinction was the almost unilateral result of

Coloss Biosciences' promises of resurrection may create a living, breathing organism. C5757’s genome may be spliced - hijacked in the name of conservation, and implanted as an embryo into an unwilling host - but it will not be a thylacine. It will exist as something else. A synthesised creature, warped and aberrated by components from separate organisms, unable to form a whole. Putting aside fantastical images of mutant thylacines or a cobbled together monster à la Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Colossal’s creature will likely be quite unremarkable. As noted by Kristofer Helgen, chief scientist at Australian Museums Research, all that is being promised is a “genetically modified dunnart.”15 The resurrection of the thylacine is a chimera - a foolish illusion; impossible to achieve, held in vain. The thylacine is dead.

Of course, there are those that believe that the thylacine never went extinct. That, when our lone female passed away in the early hours of September 7th 1936 in Beaumarris Zoo, other thylacines still lingered in the wild. Avoiding the trappings of loggers and the rifles of hunters, they managed to survive the ravages of colonisation. That their descendants - against all odds - persevere today.

I’m not quick to discount them. Recent studies have estimated that the thylacine may have continued on in the wild through until the 21st century, and some individuals may still be alive today.16 Perhaps through historic efforts to kill them and modern desperation to find them alive, they managed to stay hidden. In the dense temperate rainforests of takanya/the Tarkine maybe, or the frigid heathlands of the uninhabited South West Wilderness. Mist and dewdrops shielding their steps, maybe they slink silently through the undergrowth, undetected. Ancient gums that have cradled generations of thylacines now the refuge for the remaining few. I want to believe they’re alive. I don’t want it to end.

Or, maybe, they linger in a different space. Not in the ferny deep of lutruwita’s bushland, or a test tube in a Colossal laboratory. But in the web. Online.

Can you hear her? Through the hum of the screen?

In the internet C5757 is reborn. She might be here now. Lurking within the bandwidth, watching cautiously through layers of javascript. You can trace the imprint of her paws through your search history, and see the pattern of her stripes in the cloud. In abandoned chatrooms and long forgotten forums, you can find her. Living on in our servers. Feeding on RAM.

A fatal error has occurred.

Would you like to try again?

︎︎

I acknowledge that this work was created on the unceded lands of the Bidjigal, Gadigal, and Dharawhal clans of Dharug Ngurra. I pay my respects to Elders past and present, and recognise their ongoing connection to land, water, tradition, and culture. Sovereignty was never ceded. Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land.

1. National Museum of Australia, “Extinction of the Thylacine”. National Museum of Australia, Last updated September 9th, 2025, https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/extinction-of-thylacine

2. Angela Heathcote, “Fake or Real? This Photo of the Thylacine has Caused a Lot of Controversy”, Australian Geographic, December 13, 2018, https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/photography/2018/01/fake-or-real-this-photo-of-the-thylacine-has-caused-a-lot-of-controversy/

3. https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/extinction-of-thylacine

4. “Extinction of Thylacine”, NMA.

5. The Thylacine Museum, “History: Persecution (Page 9), Natural Worlds, http://www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/persecution/persecution_9.htm

6. Thylacine Museum, “Persecution”

7. Adam Langenberg, “Lost Remains of Last-Known Tasmanian Tiger Found at Museum, Solving ‘Zoological Mystery’”, ABC, 5th December, 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-12-05/last-tasmanian-tiger-remains-found-in-museum-cupboard/101733008

8. Langenberg, “Lost Remains Found”

9. Australia’s native wildlife were of course not ‘strange’ or 'foreign’; European colonists were the foreign presence on sovereign Aboriginal land. Australian native animals were often denigrated as ‘backward’ or ‘primitive’ in comparison to animals from Europe. Jack Ashby’s Platypus Matters explores the origins and impacts of this in great detail. Well worth a read.

10. Meg Whitfield, “Colossal Biosciences Behind Thylacine De-Extinction Effort Announces Genome Progress, But Others Call for Peer Review”, ABC, 17th October, 2024, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-10-17/tasmanian-tiger-thylacine-deextinction-project-genome-sequence/104466948

11. “Thylacine”, Colossal Laboratories & Biosciences, https://colossal.com/thylacine/

12. Museums Victoria, “Secrets From Beyond Extinction: the Tasmanian Tiger,” Museums Victoria, https://museumsvictoria.com.au/article/secrets-from-beyond-extinction-the-tasmanian-tiger/

13. Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016), 102

14. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, 101

15. Whitfield, “Thylacine De-Extinction.”

16. James Fair, “Study Suggest the Tasmanian Tiger Survived into the 21st Century”, MONGABAY, 4th February 2021, https://news.mongabay.com/2021/02/study-suggests-tasmanian-tiger-survived-into-the-21st-century/